About

Diali Cissokho & Kaira Ba's music is steeped in ancient West African griot traditions, but propelled into the 21st century by the modernizing impulses of a rock band format. Agile basslines interweave with the melodic twins of kora and electric guitar, undergirded by an explosive rhythm section of traditional percussion and trapset drums. Irrepressible dance ...

Links

Contact

Current News

- 06/25/201807/28/2018

- Aberdeen, NC

Music Talks: Diali Cissokho & Kaira Ba Carve Unexpected New Routes From West Africa to the American South

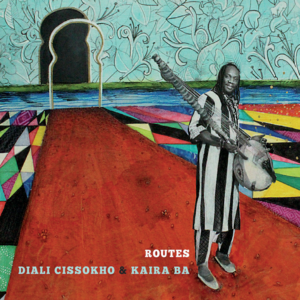

North Carolina-based Senegalese kora master Diali Cissokho took his American bandmates from Kaira Ba back to his hometown of M’bour on a long wished-for trip to record an album together, what became Routes (Twelve | Eight Records; release: June 29, 2018).

Nearly fresh off the plane, Cissokho and bassist/ producer Jonathan Henderson dashed around the port city, looking at concrete-block room after concrete-block room. “We were wondering if we’d ever find the right...

- The Phantom Tollbooth, Album review, 08/24/2018, America meets Africa again – but this time America’s a lot more assertive. I can’t think of an easier way into world music Text

- World Jazz News, Feature story, 05/14/2018, USA: Music Talks: Diali Cissokho & Kaira Ba Carve Unexpected New Routes From West Africa to the American South

- Jazz World Quest, Track pick, 05/15/2018, Jazz & World Music Albums Released in 2018 Text

- Republic of Jazz, Feature story, 05/16/2018, Music Talks: Diali Cissokho & Kaira Ba Carve Unexpected New Routes From West Africa to the American South Text

- + Show More

News

North Carolina-based Senegalese kora master Diali Cissokho took his American bandmates from Kaira Ba back to his hometown of M’bour on a long wished-for trip to record an album together, what became Routes (Twelve | Eight Records; release: June 29, 2018).

Nearly fresh off the plane, Cissokho and bassist/ producer Jonathan Henderson dashed around the port city, looking at concrete-block room after concrete-block room. “We were wondering if we’d ever find the right space,” recalls Henderson. “Then Diali ran into an old friend at the mosque. He owned a hotel and showed us this really beautiful eight-sided, rattan-paneled room on the third story. You could see the ocean. For a week, we set the studio up there, using our engineer Jason Richmond’s mobile rig. And in the courtyard outfront, we recorded the big percussion parts.” Cissokho’s musical friends and family dropped by the seaside recording studio, laying down inspired cameos.

After their Senegal sessions, the band took the tracks back to North Carolina and wove in talented local musicians, from gospel vocals (“Salsa Xalel”) to gorgeous strings (“Naamuusoo”). “We wanted to tell the story of these two places Diali has called home,” explains Henderson. “We wanted to bring North Carolina and M’bour together on the record.” They enlisted the talent of world-class violinist Jennifer Curtis, North Carolina Heritage Award-winning mandolin player Tony Williamson, jazz and gospel vocalists Shana Tucker and Tamisha Waden, the great pedal steel guitar player Eric Heywood, and a handful of local jazz instrumentalists.

The results range from high-energy dancefloor-friendly to intimate and contemplative. Cissokho’s storytelling and musical prowess give direction to Kaira Ba’s American players, whose explorations and instincts carve new paths across the Atlantic, a mutual exchange and musical conversation that easily span oceans.

{full story below}

Cissokho comes from a long line of Mande musicians tracing back to the 16th-century Mali Empire, trained to foster exchange and spark conversation, soothing hearts and rousing spirits. Born into a family of griots, Cissokho learned from an early age how to play kora, sing, and craft songs to praise patrons, recall past events, and heal intense conflicts and emotions. “Badima” pays tribute to his family and its beautiful legacy, recalling a moment when family discord resolved into harmony.

Cissokho landed in North Carolina thanks to love, falling for and marrying an American student of Senegalese music. He felt lost at first, as he tried to find his musical bearings in his new home. He went to a lot of shows, met a lot of local musicians, and finally, through trial, error, and jam sessions, connected with a quartet of local artists who got him, and whom he got. After connecting with Cissokho, drummer Austin McCall brought the group together. It included Will Ridenour, who had studied djembe and kora extensively in Senegal and Mali, on percussion. Berklee-trained jazz guitarist John Westmoreland worked closely with Diali to incorporate the interwoven kora lines into his own playing. Jonathan Henderson, an ethnomusicologist with a background in jazz and afro-diasporic styles joined on bass.

The process took time. “Our instruments had to talk to each other,” explains Cissokho. “They had to follow my key, tune into me. I didn’t know how to explain. But then they heard the melody, and they tuned to me. I started to believe, okay, it’s coming. I didn’t lose my music from back home -- it’s always here with me. We spoke a different language. But music, as my dad would say, music talks.”

The gradual process of mastering each other’s musical speech, of building real friendships, unfolded over several years. Henderson and fellow Kaira Ba bandmates mastered the rhythms and melodic arcs that formed the heart of Cissokho’s music, while Cissokho picked up on their penchant for strong arrangements and funky hooks. They learned from each other, sometimes in complex, multi-layered ways that went far deeper than jamming or teaching each other licks.

One example of the in-depth conversation between Cissokho and Kaira Ba can be heard in the string quartet of “Alla L’a Ke.” “First we recorded Diali playing the song solo on kora. Then I went on a week-long retreat up in the mountains,” Henderson says. “I transcribed the kora playing and used it as the starting point for the string quartet arrangements. When I got back, I played him the midi output from the notation software. ‘That’s my hand,’ Diali said.” Though his musical fingerprints were all over the arrangement, it took a while for Cissokho and the rest of the band to warm up to the novel sound. Yet the strings bring another, warm layer to the more conventional Afropop palette.

Kaira Ba loves to buck expectations by tapping into less appreciated sides of Senegalese music--then adding an American twist. Salsa has long had a place in Senegalese listeners’ and musicians’ hearts, and “Salsa Xalel” shines a light on the style’s widespread popularity. “Salsa is a big deal in West Africa. My dad listened to salsa and played it and danced to it,” Cissokho notes. “I knew it from my dad. When my dad didn’t get along with his wives, he would play salsa and sing to them. I’d listen to the groove and the melody, how he put his finger to the string. That’s how I got into salsa,” a style Cissokho experimented with. In Senegal, they expanded Cissokho’s song by adding balafon and talking drum (tama) to the mix. Then, back in North Carolina, the band invited singers Tucker and Waden to contribute, blending in another layer of African-heritage sound.

Though the uptempo songs on Routes lock into funky, deep pockets, making for irresistible dance tracks, other pieces stretch into more tender territory. “Saya” came to Cissokho after his beloved mother passed away: “Right when we buried her, everyone started to walk back home. I couldn’t. I stayed in the cemetery. I started to turn home and this song came to my heart. I went to my uncle’s room. He used to play kora until he grew older. I asked him if I could borrow it, because I needed to play this song. My uncle and everyone told me no, we had just buried her, but then they listened to what I played and started crying.”

Though Kaira Ba kept a light touch, they invited Eric Heywood to add arcs of pedal steel. “We wanted to get out of the way and let the song shine, in its honesty,” Henderson recounts. “That was the first take, with just kora and vocal live. While some of instrumentation on other tracks took warming up to, the pedal steel was something that Diali connected with right away. There’s an expressive quality to it, somehow reminiscent of the human voice.”

The people and places of M’bour and the North Carolina piedmont express themselves on Routes as well, not only via Cissokho’s lyrics and stories or musical performances, but in atmospheric recordings that weave in and out of tracks. Recordings of markets, nighttime courtyard jams, and beach life sneak into the mix. As do the voices and the sounds--Carolina cicadas sing at the start the first track--of Cissokho’s new home, his new roots.

“We wanted to give people a window into how we put this together. The album opens with cicadas in North Carolina, but then at the end, by ‘Night in M’bour,’ we share the rich sonic experience of being in Senegal, listening to this other world of sound, hearing sabar drumming reverberating in the distance, the children chanting the Quran at night,” reflects Henderson. “We wanted to weave these sounds in. The record ends with a live performance by Diali’s nephew Mamadou. That final track really captured our time outside the studio, hanging out and playing music and singing songs, learning from each other.”

North Carolina-based Senegalese kora master Diali Cissokho took his American bandmates from Kaira Ba back to his hometown of M’bour on a long wished-for trip to record an album together, what became Routes (Twelve | Eight Records; release: June 29, 2018).

Nearly fresh off the plane, Cissokho and bassist/ producer Jonathan Henderson dashed around the port city, looking at concrete-block room after concrete-block room. “We were wondering if we’d ever find the right space,” recalls Henderson. “Then Diali ran into an old friend at the mosque. He owned a hotel and showed us this really beautiful eight-sided, rattan-paneled room on the third story. You could see the ocean. For a week, we set the studio up there, using our engineer Jason Richmond’s mobile rig. And in the courtyard outfront, we recorded the big percussion parts.” Cissokho’s musical friends and family dropped by the seaside recording studio, laying down inspired cameos.

After their Senegal sessions, the band took the tracks back to North Carolina and wove in talented local musicians, from gospel vocals (“Salsa Xalel”) to gorgeous strings (“Naamuusoo”). “We wanted to tell the story of these two places Diali has called home,” explains Henderson. “We wanted to bring North Carolina and M’bour together on the record.” They enlisted the talent of world-class violinist Jennifer Curtis, North Carolina Heritage Award-winning mandolin player Tony Williamson, jazz and gospel vocalists Shana Tucker and Tamisha Waden, the great pedal steel guitar player Eric Heywood, and a handful of local jazz instrumentalists.

The results range from high-energy dancefloor-friendly to intimate and contemplative. Cissokho’s storytelling and musical prowess give direction to Kaira Ba’s American players, whose explorations and instincts carve new paths across the Atlantic, a mutual exchange and musical conversation that easily span oceans.

{full story below}

Cissokho comes from a long line of Mande musicians tracing back to the 16th-century Mali Empire, trained to foster exchange and spark conversation, soothing hearts and rousing spirits. Born into a family of griots, Cissokho learned from an early age how to play kora, sing, and craft songs to praise patrons, recall past events, and heal intense conflicts and emotions. “Badima” pays tribute to his family and its beautiful legacy, recalling a moment when family discord resolved into harmony.

Cissokho landed in North Carolina thanks to love, falling for and marrying an American student of Senegalese music. He felt lost at first, as he tried to find his musical bearings in his new home. He went to a lot of shows, met a lot of local musicians, and finally, through trial, error, and jam sessions, connected with a quartet of local artists who got him, and whom he got. After connecting with Cissokho, drummer Austin McCall brought the group together. It included Will Ridenour, who had studied djembe and kora extensively in Senegal and Mali, on percussion. Berklee-trained jazz guitarist John Westmoreland worked closely with Diali to incorporate the interwoven kora lines into his own playing. Jonathan Henderson, an ethnomusicologist with a background in jazz and afro-diasporic styles joined on bass.

The process took time. “Our instruments had to talk to each other,” explains Cissokho. “They had to follow my key, tune into me. I didn’t know how to explain. But then they heard the melody, and they tuned to me. I started to believe, okay, it’s coming. I didn’t lose my music from back home -- it’s always here with me. We spoke a different language. But music, as my dad would say, music talks.”

The gradual process of mastering each other’s musical speech, of building real friendships, unfolded over several years. Henderson and fellow Kaira Ba bandmates mastered the rhythms and melodic arcs that formed the heart of Cissokho’s music, while Cissokho picked up on their penchant for strong arrangements and funky hooks. They learned from each other, sometimes in complex, multi-layered ways that went far deeper than jamming or teaching each other licks.

One example of the in-depth conversation between Cissokho and Kaira Ba can be heard in the string quartet of “Alla L’a Ke.” “First we recorded Diali playing the song solo on kora. Then I went on a week-long retreat up in the mountains,” Henderson says. “I transcribed the kora playing and used it as the starting point for the string quartet arrangements. When I got back, I played him the midi output from the notation software. ‘That’s my hand,’ Diali said.” Though his musical fingerprints were all over the arrangement, it took a while for Cissokho and the rest of the band to warm up to the novel sound. Yet the strings bring another, warm layer to the more conventional Afropop palette.

Kaira Ba loves to buck expectations by tapping into less appreciated sides of Senegalese music--then adding an American twist. Salsa has long had a place in Senegalese listeners’ and musicians’ hearts, and “Salsa Xalel” shines a light on the style’s widespread popularity. “Salsa is a big deal in West Africa. My dad listened to salsa and played it and danced to it,” Cissokho notes. “I knew it from my dad. When my dad didn’t get along with his wives, he would play salsa and sing to them. I’d listen to the groove and the melody, how he put his finger to the string. That’s how I got into salsa,” a style Cissokho experimented with. In Senegal, they expanded Cissokho’s song by adding balafon and talking drum (tama) to the mix. Then, back in North Carolina, the band invited singers Tucker and Waden to contribute, blending in another layer of African-heritage sound.

Though the uptempo songs on Routes lock into funky, deep pockets, making for irresistible dance tracks, other pieces stretch into more tender territory. “Saya” came to Cissokho after his beloved mother passed away: “Right when we buried her, everyone started to walk back home. I couldn’t. I stayed in the cemetery. I started to turn home and this song came to my heart. I went to my uncle’s room. He used to play kora until he grew older. I asked him if I could borrow it, because I needed to play this song. My uncle and everyone told me no, we had just buried her, but then they listened to what I played and started crying.”

Though Kaira Ba kept a light touch, they invited Eric Heywood to add arcs of pedal steel. “We wanted to get out of the way and let the song shine, in its honesty,” Henderson recounts. “That was the first take, with just kora and vocal live. While some of instrumentation on other tracks took warming up to, the pedal steel was something that Diali connected with right away. There’s an expressive quality to it, somehow reminiscent of the human voice.”

The people and places of M’bour and the North Carolina piedmont express themselves on Routes as well, not only via Cissokho’s lyrics and stories or musical performances, but in atmospheric recordings that weave in and out of tracks. Recordings of markets, nighttime courtyard jams, and beach life sneak into the mix. As do the voices and the sounds--Carolina cicadas sing at the start the first track--of Cissokho’s new home, his new roots.

“We wanted to give people a window into how we put this together. The album opens with cicadas in North Carolina, but then at the end, by ‘Night in M’bour,’ we share the rich sonic experience of being in Senegal, listening to this other world of sound, hearing sabar drumming reverberating in the distance, the children chanting the Quran at night,” reflects Henderson. “We wanted to weave these sounds in. The record ends with a live performance by Diali’s nephew Mamadou. That final track really captured our time outside the studio, hanging out and playing music and singing songs, learning from each other.”

North Carolina-based Senegalese kora master Diali Cissokho took his American bandmates from Kaira Ba back to his hometown of M’bour on a long wished-for trip to record an album together, what became Routes (Twelve | Eight Records; release: June 29, 2018).

Nearly fresh off the plane, Cissokho and bassist/ producer Jonathan Henderson dashed around the port city, looking at concrete-block room after concrete-block room. “We were wondering if we’d ever find the right space,” recalls Henderson. “Then Diali ran into an old friend at the mosque. He owned a hotel and showed us this really beautiful eight-sided, rattan-paneled room on the third story. You could see the ocean. For a week, we set the studio up there, using our engineer Jason Richmond’s mobile rig. And in the courtyard outfront, we recorded the big percussion parts.” Cissokho’s musical friends and family dropped by the seaside recording studio, laying down inspired cameos.

After their Senegal sessions, the band took the tracks back to North Carolina and wove in talented local musicians, from gospel vocals (“Salsa Xalel”) to gorgeous strings (“Naamuusoo”). “We wanted to tell the story of these two places Diali has called home,” explains Henderson. “We wanted to bring North Carolina and M’bour together on the record.” They enlisted the talent of world-class violinist Jennifer Curtis, North Carolina Heritage Award-winning mandolin player Tony Williamson, jazz and gospel vocalists Shana Tucker and Tamisha Waden, the great pedal steel guitar player Eric Heywood, and a handful of local jazz instrumentalists.

The results range from high-energy dancefloor-friendly to intimate and contemplative. Cissokho’s storytelling and musical prowess give direction to Kaira Ba’s American players, whose explorations and instincts carve new paths across the Atlantic, a mutual exchange and musical conversation that easily span oceans.

{full story below}

Cissokho comes from a long line of Mande musicians tracing back to the 16th-century Mali Empire, trained to foster exchange and spark conversation, soothing hearts and rousing spirits. Born into a family of griots, Cissokho learned from an early age how to play kora, sing, and craft songs to praise patrons, recall past events, and heal intense conflicts and emotions. “Badima” pays tribute to his family and its beautiful legacy, recalling a moment when family discord resolved into harmony.

Cissokho landed in North Carolina thanks to love, falling for and marrying an American student of Senegalese music. He felt lost at first, as he tried to find his musical bearings in his new home. He went to a lot of shows, met a lot of local musicians, and finally, through trial, error, and jam sessions, connected with a quartet of local artists who got him, and whom he got. After connecting with Cissokho, drummer Austin McCall brought the group together. It included Will Ridenour, who had studied djembe and kora extensively in Senegal and Mali, on percussion. Berklee-trained jazz guitarist John Westmoreland worked closely with Diali to incorporate the interwoven kora lines into his own playing. Jonathan Henderson, an ethnomusicologist with a background in jazz and afro-diasporic styles joined on bass.

The process took time. “Our instruments had to talk to each other,” explains Cissokho. “They had to follow my key, tune into me. I didn’t know how to explain. But then they heard the melody, and they tuned to me. I started to believe, okay, it’s coming. I didn’t lose my music from back home -- it’s always here with me. We spoke a different language. But music, as my dad would say, music talks.”

The gradual process of mastering each other’s musical speech, of building real friendships, unfolded over several years. Henderson and fellow Kaira Ba bandmates mastered the rhythms and melodic arcs that formed the heart of Cissokho’s music, while Cissokho picked up on their penchant for strong arrangements and funky hooks. They learned from each other, sometimes in complex, multi-layered ways that went far deeper than jamming or teaching each other licks.

One example of the in-depth conversation between Cissokho and Kaira Ba can be heard in the string quartet of “Alla L’a Ke.” “First we recorded Diali playing the song solo on kora. Then I went on a week-long retreat up in the mountains,” Henderson says. “I transcribed the kora playing and used it as the starting point for the string quartet arrangements. When I got back, I played him the midi output from the notation software. ‘That’s my hand,’ Diali said.” Though his musical fingerprints were all over the arrangement, it took a while for Cissokho and the rest of the band to warm up to the novel sound. Yet the strings bring another, warm layer to the more conventional Afropop palette.

Kaira Ba loves to buck expectations by tapping into less appreciated sides of Senegalese music--then adding an American twist. Salsa has long had a place in Senegalese listeners’ and musicians’ hearts, and “Salsa Xalel” shines a light on the style’s widespread popularity. “Salsa is a big deal in West Africa. My dad listened to salsa and played it and danced to it,” Cissokho notes. “I knew it from my dad. When my dad didn’t get along with his wives, he would play salsa and sing to them. I’d listen to the groove and the melody, how he put his finger to the string. That’s how I got into salsa,” a style Cissokho experimented with. In Senegal, they expanded Cissokho’s song by adding balafon and talking drum (tama) to the mix. Then, back in North Carolina, the band invited singers Tucker and Waden to contribute, blending in another layer of African-heritage sound.

Though the uptempo songs on Routes lock into funky, deep pockets, making for irresistible dance tracks, other pieces stretch into more tender territory. “Saya” came to Cissokho after his beloved mother passed away: “Right when we buried her, everyone started to walk back home. I couldn’t. I stayed in the cemetery. I started to turn home and this song came to my heart. I went to my uncle’s room. He used to play kora until he grew older. I asked him if I could borrow it, because I needed to play this song. My uncle and everyone told me no, we had just buried her, but then they listened to what I played and started crying.”

Though Kaira Ba kept a light touch, they invited Eric Heywood to add arcs of pedal steel. “We wanted to get out of the way and let the song shine, in its honesty,” Henderson recounts. “That was the first take, with just kora and vocal live. While some of instrumentation on other tracks took warming up to, the pedal steel was something that Diali connected with right away. There’s an expressive quality to it, somehow reminiscent of the human voice.”

The people and places of M’bour and the North Carolina piedmont express themselves on Routes as well, not only via Cissokho’s lyrics and stories or musical performances, but in atmospheric recordings that weave in and out of tracks. Recordings of markets, nighttime courtyard jams, and beach life sneak into the mix. As do the voices and the sounds--Carolina cicadas sing at the start the first track--of Cissokho’s new home, his new roots.

“We wanted to give people a window into how we put this together. The album opens with cicadas in North Carolina, but then at the end, by ‘Night in M’bour,’ we share the rich sonic experience of being in Senegal, listening to this other world of sound, hearing sabar drumming reverberating in the distance, the children chanting the Quran at night,” reflects Henderson. “We wanted to weave these sounds in. The record ends with a live performance by Diali’s nephew Mamadou. That final track really captured our time outside the studio, hanging out and playing music and singing songs, learning from each other.”

North Carolina-based Senegalese kora master Diali Cissokho took his American bandmates from Kaira Ba back to his hometown of M’bour on a long wished-for trip to record an album together, what became Routes (Twelve | Eight Records; release: June 29, 2018).

Nearly fresh off the plane, Cissokho and bassist/ producer Jonathan Henderson dashed around the port city, looking at concrete-block room after concrete-block room. “We were wondering if we’d ever find the right space,” recalls Henderson. “Then Diali ran into an old friend at the mosque. He owned a hotel and showed us this really beautiful eight-sided, rattan-paneled room on the third story. You could see the ocean. For a week, we set the studio up there, using our engineer Jason Richmond’s mobile rig. And in the courtyard outfront, we recorded the big percussion parts.” Cissokho’s musical friends and family dropped by the seaside recording studio, laying down inspired cameos.

After their Senegal sessions, the band took the tracks back to North Carolina and wove in talented local musicians, from gospel vocals (“Salsa Xalel”) to gorgeous strings (“Naamuusoo”). “We wanted to tell the story of these two places Diali has called home,” explains Henderson. “We wanted to bring North Carolina and M’bour together on the record.” They enlisted the talent of world-class violinist Jennifer Curtis, North Carolina Heritage Award-winning mandolin player Tony Williamson, jazz and gospel vocalists Shana Tucker and Tamisha Waden, the great pedal steel guitar player Eric Heywood, and a handful of local jazz instrumentalists.

The results range from high-energy dancefloor-friendly to intimate and contemplative. Cissokho’s storytelling and musical prowess give direction to Kaira Ba’s American players, whose explorations and instincts carve new paths across the Atlantic, a mutual exchange and musical conversation that easily span oceans.

{full story below}

Cissokho comes from a long line of Mande musicians tracing back to the 16th-century Mali Empire, trained to foster exchange and spark conversation, soothing hearts and rousing spirits. Born into a family of griots, Cissokho learned from an early age how to play kora, sing, and craft songs to praise patrons, recall past events, and heal intense conflicts and emotions. “Badima” pays tribute to his family and its beautiful legacy, recalling a moment when family discord resolved into harmony.

Cissokho landed in North Carolina thanks to love, falling for and marrying an American student of Senegalese music. He felt lost at first, as he tried to find his musical bearings in his new home. He went to a lot of shows, met a lot of local musicians, and finally, through trial, error, and jam sessions, connected with a quartet of local artists who got him, and whom he got. After connecting with Cissokho, drummer Austin McCall brought the group together. It included Will Ridenour, who had studied djembe and kora extensively in Senegal and Mali, on percussion. Berklee-trained jazz guitarist John Westmoreland worked closely with Diali to incorporate the interwoven kora lines into his own playing. Jonathan Henderson, an ethnomusicologist with a background in jazz and afro-diasporic styles joined on bass.

The process took time. “Our instruments had to talk to each other,” explains Cissokho. “They had to follow my key, tune into me. I didn’t know how to explain. But then they heard the melody, and they tuned to me. I started to believe, okay, it’s coming. I didn’t lose my music from back home -- it’s always here with me. We spoke a different language. But music, as my dad would say, music talks.”

The gradual process of mastering each other’s musical speech, of building real friendships, unfolded over several years. Henderson and fellow Kaira Ba bandmates mastered the rhythms and melodic arcs that formed the heart of Cissokho’s music, while Cissokho picked up on their penchant for strong arrangements and funky hooks. They learned from each other, sometimes in complex, multi-layered ways that went far deeper than jamming or teaching each other licks.

One example of the in-depth conversation between Cissokho and Kaira Ba can be heard in the string quartet of “Alla L’a Ke.” “First we recorded Diali playing the song solo on kora. Then I went on a week-long retreat up in the mountains,” Henderson says. “I transcribed the kora playing and used it as the starting point for the string quartet arrangements. When I got back, I played him the midi output from the notation software. ‘That’s my hand,’ Diali said.” Though his musical fingerprints were all over the arrangement, it took a while for Cissokho and the rest of the band to warm up to the novel sound. Yet the strings bring another, warm layer to the more conventional Afropop palette.

Kaira Ba loves to buck expectations by tapping into less appreciated sides of Senegalese music--then adding an American twist. Salsa has long had a place in Senegalese listeners’ and musicians’ hearts, and “Salsa Xalel” shines a light on the style’s widespread popularity. “Salsa is a big deal in West Africa. My dad listened to salsa and played it and danced to it,” Cissokho notes. “I knew it from my dad. When my dad didn’t get along with his wives, he would play salsa and sing to them. I’d listen to the groove and the melody, how he put his finger to the string. That’s how I got into salsa,” a style Cissokho experimented with. In Senegal, they expanded Cissokho’s song by adding balafon and talking drum (tama) to the mix. Then, back in North Carolina, the band invited singers Tucker and Waden to contribute, blending in another layer of African-heritage sound.

Though the uptempo songs on Routes lock into funky, deep pockets, making for irresistible dance tracks, other pieces stretch into more tender territory. “Saya” came to Cissokho after his beloved mother passed away: “Right when we buried her, everyone started to walk back home. I couldn’t. I stayed in the cemetery. I started to turn home and this song came to my heart. I went to my uncle’s room. He used to play kora until he grew older. I asked him if I could borrow it, because I needed to play this song. My uncle and everyone told me no, we had just buried her, but then they listened to what I played and started crying.”

Though Kaira Ba kept a light touch, they invited Eric Heywood to add arcs of pedal steel. “We wanted to get out of the way and let the song shine, in its honesty,” Henderson recounts. “That was the first take, with just kora and vocal live. While some of instrumentation on other tracks took warming up to, the pedal steel was something that Diali connected with right away. There’s an expressive quality to it, somehow reminiscent of the human voice.”

The people and places of M’bour and the North Carolina piedmont express themselves on Routes as well, not only via Cissokho’s lyrics and stories or musical performances, but in atmospheric recordings that weave in and out of tracks. Recordings of markets, nighttime courtyard jams, and beach life sneak into the mix. As do the voices and the sounds--Carolina cicadas sing at the start the first track--of Cissokho’s new home, his new roots.

“We wanted to give people a window into how we put this together. The album opens with cicadas in North Carolina, but then at the end, by ‘Night in M’bour,’ we share the rich sonic experience of being in Senegal, listening to this other world of sound, hearing sabar drumming reverberating in the distance, the children chanting the Quran at night,” reflects Henderson. “We wanted to weave these sounds in. The record ends with a live performance by Diali’s nephew Mamadou. That final track really captured our time outside the studio, hanging out and playing music and singing songs, learning from each other.”

North Carolina-based Senegalese kora master Diali Cissokho took his American bandmates from Kaira Ba back to his hometown of M’bour on a long wished-for trip to record an album together, what became Routes (Twelve | Eight Records; release: June 29, 2018).

Nearly fresh off the plane, Cissokho and bassist/ producer Jonathan Henderson dashed around the port city, looking at concrete-block room after concrete-block room. “We were wondering if we’d ever find the right space,” recalls Henderson. “Then Diali ran into an old friend at the mosque. He owned a hotel and showed us this really beautiful eight-sided, rattan-paneled room on the third story. You could see the ocean. For a week, we set the studio up there, using our engineer Jason Richmond’s mobile rig. And in the courtyard outfront, we recorded the big percussion parts.” Cissokho’s musical friends and family dropped by the seaside recording studio, laying down inspired cameos.

After their Senegal sessions, the band took the tracks back to North Carolina and wove in talented local musicians, from gospel vocals (“Salsa Xalel”) to gorgeous strings (“Naamuusoo”). “We wanted to tell the story of these two places Diali has called home,” explains Henderson. “We wanted to bring North Carolina and M’bour together on the record.” They enlisted the talent of world-class violinist Jennifer Curtis, North Carolina Heritage Award-winning mandolin player Tony Williamson, jazz and gospel vocalists Shana Tucker and Tamisha Waden, the great pedal steel guitar player Eric Heywood, and a handful of local jazz instrumentalists.

The results range from high-energy dancefloor-friendly to intimate and contemplative. Cissokho’s storytelling and musical prowess give direction to Kaira Ba’s American players, whose explorations and instincts carve new paths across the Atlantic, a mutual exchange and musical conversation that easily span oceans.

{full story below}

Cissokho comes from a long line of Mande musicians tracing back to the 16th-century Mali Empire, trained to foster exchange and spark conversation, soothing hearts and rousing spirits. Born into a family of griots, Cissokho learned from an early age how to play kora, sing, and craft songs to praise patrons, recall past events, and heal intense conflicts and emotions. “Badima” pays tribute to his family and its beautiful legacy, recalling a moment when family discord resolved into harmony.

Cissokho landed in North Carolina thanks to love, falling for and marrying an American student of Senegalese music. He felt lost at first, as he tried to find his musical bearings in his new home. He went to a lot of shows, met a lot of local musicians, and finally, through trial, error, and jam sessions, connected with a quartet of local artists who got him, and whom he got. After connecting with Cissokho, drummer Austin McCall brought the group together. It included Will Ridenour, who had studied djembe and kora extensively in Senegal and Mali, on percussion. Berklee-trained jazz guitarist John Westmoreland worked closely with Diali to incorporate the interwoven kora lines into his own playing. Jonathan Henderson, an ethnomusicologist with a background in jazz and afro-diasporic styles joined on bass.

The process took time. “Our instruments had to talk to each other,” explains Cissokho. “They had to follow my key, tune into me. I didn’t know how to explain. But then they heard the melody, and they tuned to me. I started to believe, okay, it’s coming. I didn’t lose my music from back home -- it’s always here with me. We spoke a different language. But music, as my dad would say, music talks.”

The gradual process of mastering each other’s musical speech, of building real friendships, unfolded over several years. Henderson and fellow Kaira Ba bandmates mastered the rhythms and melodic arcs that formed the heart of Cissokho’s music, while Cissokho picked up on their penchant for strong arrangements and funky hooks. They learned from each other, sometimes in complex, multi-layered ways that went far deeper than jamming or teaching each other licks.

One example of the in-depth conversation between Cissokho and Kaira Ba can be heard in the string quartet of “Alla L’a Ke.” “First we recorded Diali playing the song solo on kora. Then I went on a week-long retreat up in the mountains,” Henderson says. “I transcribed the kora playing and used it as the starting point for the string quartet arrangements. When I got back, I played him the midi output from the notation software. ‘That’s my hand,’ Diali said.” Though his musical fingerprints were all over the arrangement, it took a while for Cissokho and the rest of the band to warm up to the novel sound. Yet the strings bring another, warm layer to the more conventional Afropop palette.

Kaira Ba loves to buck expectations by tapping into less appreciated sides of Senegalese music--then adding an American twist. Salsa has long had a place in Senegalese listeners’ and musicians’ hearts, and “Salsa Xalel” shines a light on the style’s widespread popularity. “Salsa is a big deal in West Africa. My dad listened to salsa and played it and danced to it,” Cissokho notes. “I knew it from my dad. When my dad didn’t get along with his wives, he would play salsa and sing to them. I’d listen to the groove and the melody, how he put his finger to the string. That’s how I got into salsa,” a style Cissokho experimented with. In Senegal, they expanded Cissokho’s song by adding balafon and talking drum (tama) to the mix. Then, back in North Carolina, the band invited singers Tucker and Waden to contribute, blending in another layer of African-heritage sound.

Though the uptempo songs on Routes lock into funky, deep pockets, making for irresistible dance tracks, other pieces stretch into more tender territory. “Saya” came to Cissokho after his beloved mother passed away: “Right when we buried her, everyone started to walk back home. I couldn’t. I stayed in the cemetery. I started to turn home and this song came to my heart. I went to my uncle’s room. He used to play kora until he grew older. I asked him if I could borrow it, because I needed to play this song. My uncle and everyone told me no, we had just buried her, but then they listened to what I played and started crying.”

Though Kaira Ba kept a light touch, they invited Eric Heywood to add arcs of pedal steel. “We wanted to get out of the way and let the song shine, in its honesty,” Henderson recounts. “That was the first take, with just kora and vocal live. While some of instrumentation on other tracks took warming up to, the pedal steel was something that Diali connected with right away. There’s an expressive quality to it, somehow reminiscent of the human voice.”

The people and places of M’bour and the North Carolina piedmont express themselves on Routes as well, not only via Cissokho’s lyrics and stories or musical performances, but in atmospheric recordings that weave in and out of tracks. Recordings of markets, nighttime courtyard jams, and beach life sneak into the mix. As do the voices and the sounds--Carolina cicadas sing at the start the first track--of Cissokho’s new home, his new roots.

“We wanted to give people a window into how we put this together. The album opens with cicadas in North Carolina, but then at the end, by ‘Night in M’bour,’ we share the rich sonic experience of being in Senegal, listening to this other world of sound, hearing sabar drumming reverberating in the distance, the children chanting the Quran at night,” reflects Henderson. “We wanted to weave these sounds in. The record ends with a live performance by Diali’s nephew Mamadou. That final track really captured our time outside the studio, hanging out and playing music and singing songs, learning from each other.”